What follows is an abridged narration of the extraordinary death of Saint Teresa Margaret.[1]

Four months before her death, Teresa Margaret had made a pack with Sr. Adelaide, an elderly nun she was caring for. The pact was that when she died, Sr. Adelaide would ask God “to permit Sister Teresa Margaret to join her quickly in order that she may love Him without hindrance for all eternity and be fully united with the fount of divine charity.” Less than four months after this incident, Teresa Margaret was indeed with Christ in God. No one is sure but it is believed that the cause of Teresa Margaret’s death was strangulated hernia. If the cause of her death actually was hernia, it is more than likely that it was in lifting the heavy, inert body of Sister Adelaide that she strained herself; in which case, it provides a delightful “seal” to their simple pact.

It is not easy to decide that at this stage she had a definite premonition of the imminence of her death, but a strange incident is recorded at about the same time. A former acquaintance, Teresa Rinuccini, who was about to enter the Benedictine Monastery of St. Apollonia, had been doing the rounds of the convents in Florence, making the customary conventional farewell visits. On leaving the Carmel parlor where she had been talking to Teresa Margaret, Teresa said: “Before taking the habit, I will come and see you once more.”

“If you can see me,” was the enigmatic reply.

“Why, what do you mean?” asked the visitor, surprised. “Will Mother Prioress be displeased if I visit you again?”

But Teresa Margaret changed the subject, and would not explain her cryptic remark. Yet her unexpected prediction was fulfilled. Before Teresa could make a second call, Teresa Margaret was dead...

On Sunday, the 4th of March, she asked Father Ildefonse to allow her to make a general confession, as though it were to be the last of her life, and to receive Communion the following morning in the same dispositions. Whether or not she had any presentiment that this was indeed to be her Viaticum one cannot know; but in the event it proved to be so.

Teresa Margaret was twenty-two years and eight months of age, in excellent health, never having had any serious illness or even the threat of one. She was tall, well-built, robust, with a clear, fresh complexion and vivacious manner. The overwork and lack of sleep during the past few years had left no trace of physical exhaustion; she was bright, alert, and active. In fact, many marveled at her resilience and stamina, and Mother Anna Maria once remarked that she seemed to thrive on hard work, which had the effect of strengthening rather than fatiguing her.

Yet in the full bloom of healthy, young womanhood, she suddenly and inexplicably made these elaborate preparations for an imminent and precipitate death.

[It was March] The Lenten fast had not ended, and the evening meal was quickly disposed of. When Teresa Margaret reached the refectory, the community had finished their collation and departed, dispersing to perform their various chores before assembling for evening recreation. There was a piece of fruit and some bread under her folded napkin. She went to the serving hatch and fetched her bowl of soup from the kitchen where it had been left to keep hot and took her seat in the otherwise deserted room. Immediately as she began to eat the simple meal, an acute abdominal pain almost doubled her up. She rose to leave the refectory, but realized that she could not manage to climb the stairs to her cell. Entering a room nearby, she waited until the first violence of the attack had passed, then made her way upstairs. As she closed the door of her cell another spasm overwhelmed her, and she fell on to the floor, unable to reach the bed on the opposite side of the room.

Sister Mary Victoria, who was assistant infirmarian, happened to pass through the corridor just in time to hear Teresa Margaret’s call for help. Entering, she found her lying on the floor, writhing in pain. Within a matter of minutes she had summoned help, and, assisted by many hands, the sufferer was undressed and put into bed and the doctor summoned. He was not alarmed, but merely diagnosed a bout of colic - extremely painful, he agreed, but in no way serious. He prescribed a mild sedative, and advised that she should drink plenty of liquid. Then he left, with the assurance that if she followed these directions the colic would pass and there would be no complications.

Teresa Margaret did not sleep at all during the night, and she tried to lie still so as not to disturb those in the adjoining cells… With her usual exactitude she followed the doctor’s direction quite literally, and consumed an amazing quantity of liquid. Earlier in the evening she had been given broth and barley-water, and during the night two flasks, one of well water and another of mineral water, had been left with her; she drank the entire contents of both. It is hardly surprising that this course of hydro-therapy increased rather than lessened her sufferings. Her face and body were bathed in perspiration, but when Mother Anna Maria came first thing in the morning to see her, she seemed to have taken a slight turn for the better. She was less oppressed by pain, and seemed even inclined to talk a little.

Later in the morning Doctor Pellegrini returned, but as soon as he saw the patient his optimism evaporated. By this time her internal organs had become paralyzed, and after an examination he announced gravely that he would have to call in the services of a surgeon … the remedy for all ills seemed to be, when in doubt, draw some blood. Leeches were applied as relief for the most astonishingly varied ailments from asthma to sunstroke. So now the medicos proceeded to bleed Teresa Margaret’s left foot. A vein was opened, and there was a sluggish flow of congealed blood. And then for the first time it dawned upon Doctor Romiti the surgeon, how grave her condition was. Taking Sister Magdalene aside, he advised that the sister should receive the Last Sacraments without delay. She, however, felt that this was not necessary, and was reluctant to send for a priest because of the patient’s continued vomiting. Also Sister Teresa Margaret’s pain appeared to have lessened, and she suggested that instead of preparing for her death, he should endeavor to cure her. The seeming asperity of this reply was probably due to anxiety, but she passed on his message to the Prioress, who seemed to share the infirmarian’s opinion, for, strangely, none of them made any attempt to have a priest summoned.

The apparent improvement in her condition was, in fact, due to an internal hemorrhage which gave temporary relief to the congested organs, but nobody suspected this. The spasms of pain lessened, but only because she herself was growing rapidly weaker, and her general condition deteriorating alarmingly.

The patient offered no comment, nor did she ask for the Last Sacraments. She seemed to have had a premonition of this when making her last Communion “as Viaticum” the previous Sunday. She held her crucifix in her hands, from time to time pressing her lips to the five wounds, and invoking the names of Jesus and Mary, but she continued to pray and suffer, as always, in silence.

By 3 p.m. her strength was almost exhausted, and her face had assumed an alarmingly livid hue. Thoroughly frightened now, the Prioress sent hastily for Father Covari, a Dominican, who was then extraordinary confessor to the convent. He arrived in time to anoint the young nun, pronouncing in the name of the Church those portentous words of release which down the centuries have echoed for the departing soul the cry of the dying Christ: “Into thy hands I commend my spirit.” “Go forth, Christian soul, from this sinful world, in the name of God the Father Almighty who created you; in the name of Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, who suffered and died for you; in the name of the Holy Ghost, who sanctified you.”

Silent and uncomplaining to the end, with her crucifix pressed to her lips and her head slightly turned towards the Blessed Sacrament, Teresa Margaret took her flight to God.

All the nuns, kneeling huddled against each other in the confined space of the little cell, seemed stunned with the suddenness and unexpectedness of it all. A passing fit of colic ... in a few hours they had expected to see her moving once more through the corridors, serene and kindly as ever. The Prioress’ hands trembled as she closed the door after the departing community.

“Mother Anna Maria,” she said quietly, laying a detaining hand on the other’s arm, and drawing her aside. The two stood gazing down on the familiar face, quiet and still now, but almost unrecognizable under that ghastly discoloration. They turned the bedclothes back. The hands and feet were almost black. Her body seemed to be decomposing almost under their eyes.

“You must arrange for the funeral without delay, Mother,” said Mother Anna Maria quietly. “It would be most unwise to leave her body for any length of time.”

“Yes, but the obsequies ...?”

“There’s nothing to be done but hurry them forward.”

Deftly, and as quickly as possible, they clothed the already rigid body in the serge habit and enfolded it in the white choir mantle, now to be her shroud. Her billet of profession and crucifix were placed in the still hands folded on her breast, and a wreath of white flowers laid on her head over the black veil.

Suddenly the complete silence that hung heavily over the monastery was shattered by the sound of the house bell. At the summons for which all had been waiting, the community assembled quickly, wearing their choir mantles and holding lighted candles to form a procession in the cell, where the cross-bearer stood at the head of the sister who, twenty-four hours before, had been walking down this corridor. It was not easy to concentrate on the prayers with their reiterated reminders that it is death which, opening onto infinite horizons, gives life its ultimate meaning and purpose.

“Deliver me, Lord, from everlasting death in that dread day when heaven and earth will rock and thou wilt come to judge the world by fire. I tremble and am full of fear as I await the day of reckoning, that day of wrath, calamity, and sorrow...

Reverently they laid the pallet on the simple bier - two trestles covered with a black cloth - at each corner of which stood a large candlestick in which mournful brown candles flickered sullenly. The bare feet were near the open grille, and two of the nuns took their places, kneeling beside the almost unrecognizable head of their deceased sister, to begin the perpetual vigil which would end only when they laid her body in the tomb.

As the Prioress sprinkled the still form with holy water, she uttered a silent, unrubrical prayer that the rapidly approaching corruption of that once lovely body would be arrested until tomorrow, so that no unseemly accident should mar the grave solemnity of the ceremonies.

The bier was raised, and slowly the procession wended its way to the crypt for the burial. And now, after a lifetime of silent self-effacement, God lifted the veil beneath which His humble, unassuming spouse had so long concealed herself from all eyes. She was His, and He had a mission and message to pass on to us through her. This He now proclaimed, in the words of Pope Pius XI, “with that powerful voice of miracles, which is indeed His voice.”

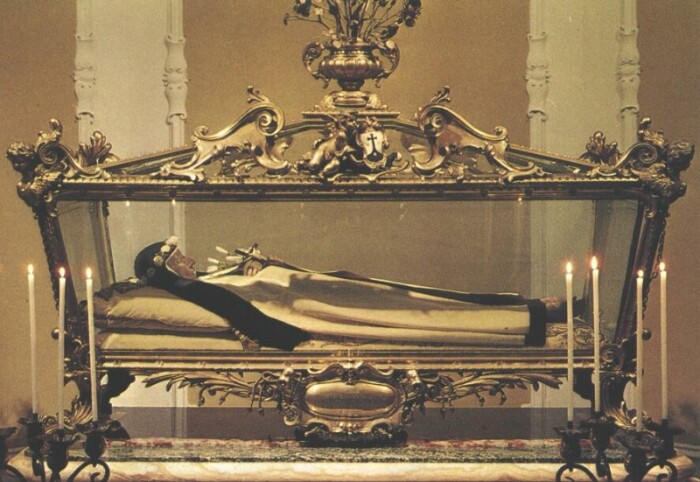

Surely, of all the wonders worked by Almighty God through this most unassuming instrument, none has been more outstanding than the preservation of her own body, after the apparent symptoms of early decomposition that everyone had observed with such alarm. Yet now, as they entered the vault, all noticed that there was another change taking place in the face; the alarming blue-black discoloration was much less pronounced, and, temporarily, the burial was postponed. Within a few hours another examination revealed that face, hands, and feet had regained their natural coloring, and the nuns felt immensely consoled to see that lovely, childlike face looking once more as they had always known it in life.

They begged the Provincial’s permission to leave her unburied until the next day, a request which he, dumbfounded at this astonishing reversal of natural processes, readily granted. The final burial of the body was arranged for the evening of the 9th of March, fifty-two hours after her death. By that time her skin tint was as natural as when in life and full health, and the limbs, which had been so rigid that dressing her in the habit had been a difficult task, were flexible and could now be moved with ease.

This was all so unprecedented that the coffin was permitted to remain open. The nuns, the Provincial, several priests and doctors all saw and testified to the fact that the body was as lifelike as if she were sleeping, and there was not the least visible evidence of corruption or decay. Her face regained its healthy appearance, there was color in her cheeks. Suddenly the real depth and wealth of the hidden, silent, self-effacing life that had been lived in their midst, in charity, humility and never-failing kindness which each had experienced at some time, dawned in full force on the nuns, when they understood the import of what was happening. Mother Victoria, who had been Prioress in 1766 and received the profession of this young nun, and had later been the recipient of her loving ministrations in the infirmary, suggested that a portrait should be painted before the eventual burial. This was unanimously agreed to, and Ann Piattoli,[2] a portrait painter of Florence, was taken down to the crypt to capture forever the features that looked so serenely life-like in death.

The Carmel burial vault was a scene of much coming and going during these days, and had assumed anything but a mournful atmosphere. By the time the painting was completed, a hitherto unnoticed fragrance was detected about the crypt. The flowers that still remained near the bier had withered, and fell to dust when touched. But the fragrance persisted, and grew in strength, pervading the whole chamber. And then, miles away in Arezzo, Camilla Redi also became aware of the elusive perfume of narcissi, so beloved by her Anna Maria, which noticeably clung to certain parts of the house - the room formerly occupied by Anna, the clothes she had worn, the golden hair cut from her head on the day of her investiture ... “The odor of sanctity,” Sister Teresa Margaret had once laughingly called this perfume, and indeed it now proved to be so.

Several times her body was visited by the surgeon, Doctor Romiti. On the fourth occasion, which was about a week after her death, he testified that the complete absence of any sign of decomposition was not a natural event, and he advised that the proper ecclesiastical authority should be informed of the prodigy, which must have a supernatural cause.

Mgr. Francis Icontri, Archbishop of Florence, was accordingly approached by a priest attached to the Carmel, Father Augustine Losi. His Grace did not seem particularly impressed, thinking no doubt that the nuns’ imagination had been at work. However, he decided to investigate the matter in person, and either confirm the marvel or squash the rumor. But he allowed another week to pass before taking any action.

On March 21st, a fortnight after Teresa Margaret’s death, he made an official visit, accompanied by a Canon, the Chancellor, and three priests from the Cathedral. There had been ample time for the natural processes of decay and dissolution to complete their work upon the body, and if, as claimed, there was no sign of corruption, it would indeed seem that a supernatural power held them in check.

His Grace descended into the crypt at about 4 p.m., accompanied by his own priests, the Carmelite Provincial and another friar, two doctors and the surgeon. Three nuns were present, including Mother Anna Maria and Sister Magdalene, the infirmarian. The doctors again examined the body, which had the appearance of a child who had just fallen into a relaxed sleep. The incision on her left foot, which had been made for the “bloodletting” was quite fresh, and her skin clear and rosy. The doctors conferred together, and finally informed the Archbishop that the condition of the body could only be regarded as miraculous. Then Mother Anna Maria records an incident which impressed her deeply:

“All were speaking of the prodigy, when the Archbishop arose, and himself uncovered the face of our dead sister. He stood there, looking at it very fixedly, startled to see the blue eyes slightly open and the whole face seemingly relaxed as one in a light but peaceful slumber.”

Did he, one wonders, recall this young girl who had knelt before him only thirteen years previously, when as a student at St. Apollonia’s, he had sealed her with the sacrament of Confirmation?

The surgeon noticed a little moisture that had gathered on her upper lip below the nostril, and wiped it off with a piece of cloth. He then smelled it, with the thought that here indeed would be a definite proof. It emitted so sweet an odor that he immediately offered it to His Grace, who stated that he also perceived “a heavenly fragrance.”

The coffin was then closed and sealed by the Archbishop, who left the crypt to visit the Prioress, at that time indisposed and confined to bed, and give her the consolation of his blessing.

“They are all elated by the great treasure you possess,” he told her, “and I too am very happy that we have so wonderful a thing in our midst. I believe it is indeed a miracle, and yet I do not think that we have yet witnessed the greatest miracle of all. In years to come she will be seen again, and those who will still be alive then shall have a great consolation.”

“Did your Grace perceive anything extraordinary?” the Prioress enquired.

“Extraordinary! Indeed, it is a miracle to see a body completely flexible after death, the eyes those of a living person, the complexion that of one in the best of health. Why, even the soles of her feet appear so lifelike that she might have been walking about a few minutes ago. She appears to be asleep. There is no odor of decay, but on the contrary a most delightful fragrance. Indeed, it is the odor of sanctity.”

That day the coffin was finally closed with twelve nails, and secured by eight episcopal seals in red wax upon black and white linen tapes. It was then placed inside a large cypress coffin, with a parchment giving the name of the deceased. The coffin was firmly placed in a niche over the door of the crypt, and a small metal plate, according to the simple Carmelite custom, recorded:

“Sister Teresa Margaret of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, died on the 7th of March, 1770, in the twenty-third year of her age, and the fourth year of her religious profession.”

The incorrupt body of St. Teresa Margaret is on view in her Carmelite Convent at:

Carmelitane Scalze

Via de' Bruni, 12

50139 Firenze

The home in which St. Teresa Margaret grew up is now a Carmelite Convent at:

Carmelitane Scalze

Via S. Francesco Redi, 17

52100 Arezzo

[1] This narration is taken from the books God is Love (1964 edition) and From the Sacred Heart to the Trinity.

[2] On seeing this portrait the father of St. Teresa Margaret remarked, I found in it all that my Dearest was in life...”